UM biologist part of institute studying species’ resiliency against disease

This green tree frog in Louisiana is part of a project University of Mississippi biologist Michel Ohmer participated in via a Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program grant through the Department of Defense. Ohmer and a team of scientists from 11 universities are using a five-year National Science Foundation grant to study how frogs and other amphibians resist pathogens and environmental change to learn how humans can do the same. Photo by Michel Ohmer

October 13, 2021 by

Humans have a lot to learn from amphibians.

This class of animals – frogs, salamanders and caecilians – has been decimated by the emergence of new infectious diseases, along with human-caused damage to their ecosystems. Yet, some species have bounced back, and researchers are wondering if there’s a lesson for humanity in the resiliency of amphibians.

To study this rebound and what humans can learn from it, a University of Mississippi biologist and a group of research peers have launched a new institute funded by a five-year, $12.5 million National Science Foundation grant.

Based at the University of Pittsburgh, the Resilience Institute Bridging Biological Training and Research, or RIBBiTR, includes researchers at 11 universities, including Michel Ohmer, an assistant professor of biology at UM.

Biology professor Michel Ohmer is a member of the Resilience Institute Bridging Biological Training and Research, a team of scientists based at the University of Pittsburgh and working to study amphibians’ resilience to disease. Photo courtesy Michel Ohmer

“Amphibians are experiencing a pandemic of their own, resulting in catastrophic amphibian declines,” said Ohmer, who joined the UM faculty in August. “Given the worldwide reach of the chytrid fungal pathogen and the wide array of species impacted, amphibians are a perfect system for studying resilience to disease.

“Many amphibian communities were decimated, and many species went extinct, but since then, we have also seen some remarkable recoveries. This provides a natural experiment to understand how and why certain populations are resilient to disease and anthropogenic change across many regions and communities.

“This is incredibly relevant today as we face multiple global crises including a pandemic, biodiversity loss and climate change. Understanding what makes some populations resilient, and what factors into that resilience, is incredibly important.”

Housed in Pitt’s Pymatuning Laboratory of Ecology, the institute also involves researchers at the University of Alabama; University of California at Berkeley; University of California at Santa Barbara; University of Massachusetts at Boston; University of Nevada at Reno; Temple University; Texas Tech University; University of Tennessee; and Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

“My part of this research partnership involves using measurements of amphibian thermal traits and exploring questions such as: Under what temperatures can these species survive? What are the optimal temperatures for performance?” Ohmer said.

“I’ll use those measurements in combination with measures of microclimate – the climate experienced by the amphibian in its environment – to make predictions of when and where amphibians will be most susceptible to climate change and disease. I will be leading experimental work at each of our field sites, as well as running empirical studies with focal species at the University of Mississippi.”

Pitt’s Corinne Richards-Zawacki, professor in ecology and evolutionary biology in the Kenneth P. Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences, is the principal investigator and leads the institute.

The institute will study amphibians from sites in Brazil, Panama, the Sierra Nevada mountain range in California and the Pymatuning Lab, which is a Pitt research lab and field station in northwestern Pennsylvania, led by Richards-Zawacki. The researchers will use pioneering approaches to tracking amphibians, such as collecting tiny traces of DNA from the environment and automatically picking up the sound of frog calls.

This Southern leopard frog was photographed in Louisiana while UM biology professor Michel Ohmer was investigating an amphibian-pathogen system across the U.S. and under current and future climate scenarios. Photo by Michel Ohmer

“Because we have lots of data over time from around the world on amphibians who are doing better now than they were after the initial disease outbreaks, they are perfect for studying resilience,” Richards-Zawacki said. “We can ask many questions: What mechanisms make them able to live with their pathogens? Are the pathogens changing? What is the impact of different environments?

“If we understand how the relationship has changed between the species and the threat, we can consider how resilience can be applied to other biological systems.”

Ohmer first got involved with many of the institute’s researchers as part of a Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program grant through the Department of Defense.

“We were investigating this amphibian-pathogen system across the U.S. and under current and future climate scenarios,” said Ohmer, whose research interests include amphibian biology and disease ecology, ecophysiology, global change and conservation biology.

“I am excited to continue to work with these collaborators, as well as expand our partnership to a broader number of institutions and field study locations worldwide, to understand the many ways in which amphibian populations can demonstrate resilience in the face of multiple stressors.”

The institute is part of the NSF’s strategy to create large research teams across disciplines and regions to investigate “rules of life” principles – fundamental life processes ranging from biomes to the Earth.

The award, No. 2120084, is titled “Uncovering mechanisms of amphibian resilience to global change from molecules to landscapes.”

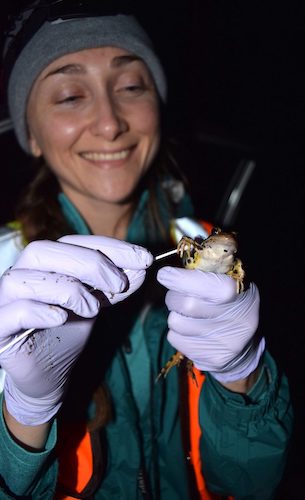

Michel Ohmer works with a frog in the field. Photo courtesy Michel Ohmer

“I’m elated that the NSF has funded the work proposed by the RIBBiTR team,” said Brice Noonan, UM acting chair and associate professor of biology. “The work proposed by Dr. Ohmer and colleagues is clearly relevant as our species struggles through its own pandemic.

“By exploring how frogs have survived and managed to coexist with emerging pathogens that have had devastating effects on their populations we can better understand the ways living organisms, including humans, are able to adapt to these challenging environmental conditions.”

Beyond the biology research, the institute’s team is charged with developing curriculum and programs that will train the next generation of biologists.

At Ole Miss, that means Ohmer will work with Erik Hom, an associate professor of biology, to develop high school research and mentoring experiences that explore the concept of resilience in ecology. The initiative will be part of the A Research Immersive STEM Experience at the University of Mississippi program.

“My collaborators and I will also develop education modules in the form of student-directed research projects that will contribute to a growing body of knowledge on amphibian thermal physiology,” Ohmer said. “Finally, I look forward to training graduate students and postdocs in ecophysiology both in Mississippi and on location at our field sites as a part of the institute.

“It is incredibly important that we work to broaden participation in science and work to train the next generation of biologists to work in integrative ways as this is the future of scientific discovery. The greater the diversity of backgrounds and experiences, and the more that we elevate underrepresented voices, the stronger and more transformative our science will be.”