Michel Ohmer, assistant professor of biology

Dr. Michel Ohmer has joined the University of Mississippi as an assistant professor in the Department of Biology. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Queensland in Australia, and then went on to do postdoctoral work at the University of Pittsburgh with Dr. Cori Richards-Zawacki. Before coming to UM, she was a postdoctoral fellow at the Living Earth Collaborative at Washington University in St. Louis, where she investigated the role of intraspecific variation in thermal traits on climate suitability predictions for amphibian populations impacted by disease. Her research program is in global change ecophysiology and disease ecology, with a focus on amphibians and their conservation.

What is your primary research focus? Why or how did you become interested in this focus?

I study disease ecology, ecophysiology, and conservation biology. I primarily work with amphibians, which have experienced dramatic declines worldwide as the result of multiple interacting stressors. I have always been fascinated by amphibians and loved catching tadpoles and frogs in the local pond and exploring the natural areas by my house as a child. When I learned about the amphibian extinction crisis as an undergraduate, particularly how frogs were declining in pristine protected areas due to disease, I knew that this was an area of research that I wanted to pursue, in the hopes that my research would benefit conservation actions.

What have you been working on in the years leading up to your start at UM?

My work focuses on how and why individuals, populations, and species have varied responses to environmental stressors, and in particular, disease. I use ecophysiological, immunological, and modeling tools to investigate these differences. Just prior to coming to UM, I was a Living Earth Collaborative postdoctoral fellow at Washington University in St. Louis, where I was working to predict regions of refuge from both climate change and disease for a declining frog species in the central US. I am interested in whether intraspecific variation in thermal physiology may impact our predictions for how this species will fare as the climate warms. I am excited to continue and expand upon this research at UM.

What experiences do you hope to gain at UM that you haven’t had the opportunity to, previously?

I am looking forward to working with undergraduate and graduate students not only through the classes that I will be teaching, but also in the laboratory and out in the field, as I work to create an inclusive research laboratory group where everyone feels welcome. I am also excited to interact and collaborate with faculty in the UM Biology department, and to expand my field research to both the local field station and natural areas around the state. I am lucky that Mississippi is home to a wonderful diversity of amphibian species!

How will you transition your research to the UM biology department?

I am excited to bring my research program to UM. My laboratory and animal rooms are currently being renovated to include controlled temperature chambers, molecular laboratory spaces, and behavioral assay rooms, which will equip my lab members to do cutting edge ecophysiological research. In addition, my research interests overlap with those of many of the Biology faculty, paving the way for future fruitful collaborations.

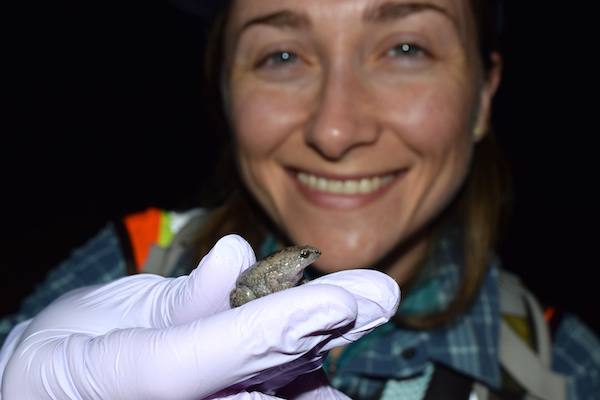

Dr. Ohmer in the field

Tell about the class you’ll be teaching.

Next semester I will be teaching BISC 330, or Introductory Physiology. While this course is primarily focused on human physiology, I will be drawing on my background in animal ecophysiology to bring a comparative angle to the curriculum. This course is one of the core courses of the Biology major, and I look forward to interacting with students pursuing a range of career goals.

What else will you be doing at UM (this semester and in the future)?

I am a part of new, recently funded NSF Biology Integration Institute (there will be a news release soon) that will be working to uncover the mechanisms of resilience to disease, using the amphibian-fungal pathogen system as a model. Amphibian populations have declined worldwide as a result of the amphibian chytrid fungus, which causes the disease chytridiomycosis. Since this disease was first described 30 years ago, some populations have begun to rebound. We will be studying how and why some populations are resilient to disease, and in particular, I will be using ecophysiological and modeling tools to understand how climate change may modulate this resilience.

What interests you other than science? Any hobbies or extracurriculars?

In addition to science, I love art and the outdoors. I am fond of painting, dance, and photography. I also enjoy hiking and backpacking, and I love traveling and exploring new places with my family: my partner Jeff, our son Emerson, and our pup, Darcy.