UM biologist receives National Institutes of Health award to study heart formation

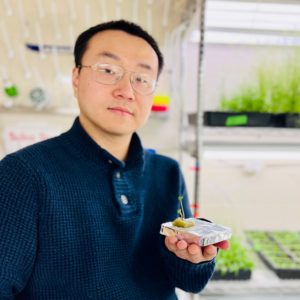

Biology professor Joshua Bloomekatz (left) and doctoral student Rabina Shrestha examine a tank of zebrafish. Bloomekatz and his research team are using the fish, which has heart processes similar to humans, to study how cardiac cells rearrange themselves to form structures of the heart. Photo by Kevin Bain/Ole Miss Digital Imaging Services

OXFORD, Miss. – A University of Mississippi biologist is asking big questions about the development of the human heart, and a new National Institutes of Health grant may help him find the answers.

“When I think about life’s big picture, I think one of the great mysteries is how we go from a single cell to a whole human being,” said Joshua Bloomekatz, assistant professor of biology. “Our research looks at how the heart develops – how embryos go from a group of amorphous cells to having a pumping, beating heart.”

The NIH awarded Bloomekatz $411,969 to conduct a new study that could help scientists understand why congenital heart defects, or CHDs, occur. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CHDs affect about 40,000 births per year. This is caused by defects in the heart’s development, Bloomekatz said.

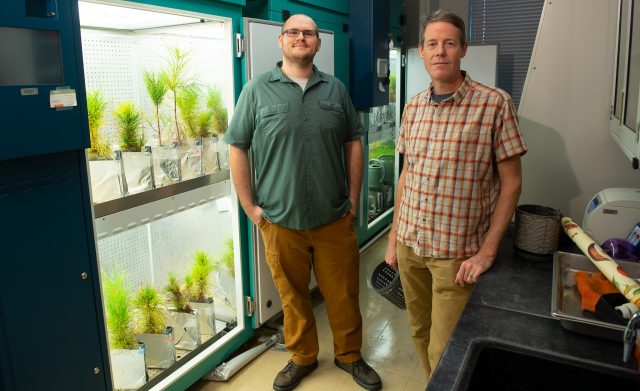

Zebrafish embryos develop externally, or outside the maternal body. UM professor Joshua Bloomekatz is filming the fish’s heart development in real time as its cells move. Submitted photo

“This is fundamental biology in the sense that if we learn how things normally happen – how cells form and how cell movement happens – we can take this knowledge and use it when things go wrong,” he said.

“If we can understand the basic fundamental processes that create form in the heart, we can hopefully contribute to the understanding of how congenital heart defects occur.”

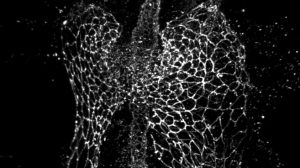

The study investigates how cardiac cells rearrange themselves to form structures of the heart, specifically the heart tube.

To answer this question, Bloomekatz and his team will observe zebrafish embryos. Surprisingly, this freshwater fish’s heart has similar processes to human hearts.

“The cool thing about the zebrafish embryo is that development happens externally outside of the maternal body,” he said. “We can film the development in real time as the cells move.”

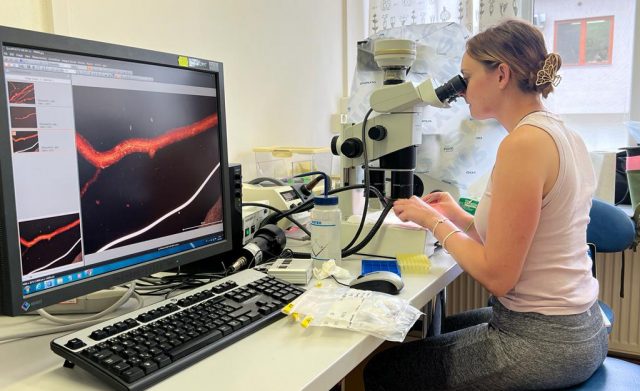

The study uses a high-resolution microscope at the GlyCORE Imaging Core. The core gives investigators access to a wide range of advanced microscopy instrumentation.

Bloomekatz said another important aspect of this project is an emphasis on educational research experiences. He has invited both undergraduate and graduate students to participate in the innovative study.

Rabina Shrestha, fifth-year biology doctoral student from Kathmandu, Nepal, is studying intercellular signaling that regulates the movement of myocardial cells during heart tube formation. She said that this knowledge could have broad applications.

Pictured here are different shapes of cardiomyocytes during heart tube formation. Biology professor Joshua Bloomekatz and his team will investigate how these cells rearrange to form the heart tube. Submitted image

“Collective cell migration occurs at several stages of cardiac development, including during heart tube assembly, valvulogenesis, the initiation of trabeculation and it is also important during directional migration of several other organ progenitors such as the mesoderm and neural crest cells,” Shrestha said.

“Thus, our findings are likely applicable to a broad range of developmental processes and disease.”

Christian Miller, a senior biomedical engineering student from Bentonville, Arkansas, is assisting Bloomekatz by 3D-printing molds that hold and orient the zebrafish embryos so that they can be imaged as they develop.

“This is meaningful research because of the impact it has on our own understanding of heart development, and this understanding’s contribution to helping stop the leading cause of death in the United States: cardiovascular disease” Miller said.

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award No. R15HD108782. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.